Firearm Suicide and COVID-19

Mitigating Risk During a Pandemic

We are living in unprecedented times. Today Americans are under a cloud of uncertainty and stress as we live through the COVID-19 pandemic. Seven out of ten Americans report their lives have been disrupted “a lot” or “some” by the coronavirus outbreak. People are suddenly isolated by physical distancing practices and quarantines, which may lead to loneliness, economic uncertainty, escalating stress and distress, and risky alcohol use — all of which are risk factors for suicide. As our world faces one public health emergency in COVID-19, we know that firearm suicide remains its own public health crisis — which could be exacerbated by COVID-19.

The following memo outlines what the current research says about the risk factors for suicide that may become more prevalent during COVID-19 and share the interventions available to help mitigate that risk. For example, strengthening economic supports by giving Americans subsidies and robust unemployment benefits, sharing support lines to be used when needed, ensuring alcohol usage does not become risky, and taking time to connect with loved ones by phone or online are all important suicide prevention strategies. Importantly, reducing access to lethal means, including firearms, can mean the difference between life and death for a person with increased risk factors. As we check in with our loved ones to counter social isolation or see if we can pick up extra groceries for our most at-risk friends, asking about their firearms access and making sure firearms are safely stored –theirs and our own– are critical steps we can take to support well-being through this difficult time.

Suicide Risk Factors During COVID-19

A suicide risk factor is any characteristic or exposure that increases the likelihood a person may attempt or die by suicide. A variety of factors influence an individual’s risk of suicide, and suicide risk can fluctuate due to the number and intensity of risk and protective factors (those that decrease risk) experienced.

Feelings of loneliness, social isolation, stressful life events, risky alcohol use, and access to lethal means (i.e. firearms) all increase the risk for suicide. The unprecedented pandemic we are all living through may lead to a number of these suicide risk factors being exacerbated. Additionally, people who are already vulnerable to suicidality (those who are unemployed, experiencing depression or anxiety, and those who are isolated) may be at even greater risk for suicidality during COVID-19.

As COVID-19 exacerbates risk factors for suicidality, it is more important than ever to take a comprehensive approach to preventing suicide. Given that one in three homes has a firearm, and with the majority of Americans stuck at home trying to prevent the spread of the virus, it is more important than ever before to emphasize and mitigate the role of firearms in suicide prevention.

Isolation + Loneliness

Many Americans were lonely or isolated prior to COVID-19. A 2018 poll conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation and The Economist poll found 22% of Americans report “always or often feel[ing] lonely, or lack companionship, or else feel[ing] left out or isolated.” Further, nearly 36 million Americans live alone. Due to COVID-19, isolation and loneliness may be even more common, as more than 90% of the United States population, about 300 million people, is under stay at home orders as of April 6. For many of us, this dramatic change to our regular schedules means we are not seeing friends, families, or coworkers like we’re used to. We aren’t able to go to the gym or enjoy our hobbies out of the house. We have lost the normalcy of our daily routines and this physical distancing and isolation very well may lead to increased loneliness.

Dating back to the 1800s, lack of social connectedness has been considered a risk factor for suicide. Both the objective condition of being alone and the subjective feeling of feeling alone are associated with suicidal ideation and attempts.

While we are in an unprecedented time of physical distancing and isolation, there is research on the psychological outcomes of people quarantined during the outbreaks of SARS, H1N1 flu, Ebola, and other infectious diseases that inform our understanding of the psychological outcomes we are likely to be facing in the era of COVID-19. The analyses found that many of these individuals experienced short and long-term mental health problems, including psychological distress, post-traumatic stress, insomnia, emotional exhaustion, and risky substance use. Notably, quarantines lasting longer than 10 days further exacerbated the risk of psychological problems.

A population to specifically take note of is the elderly. Our elders are at heightened risk for severe coronavirus outcomes and already experience especially high rates of social isolation and loneliness. Further, suicide risk is highest among older men and loneliness and social isolation are risk factors for suicidal ideation, particularly among the elderly. Special care to reduce risk of exposure to COVID-19, while also mitigating suicide risk among our elders, is critical for their health and well-being.

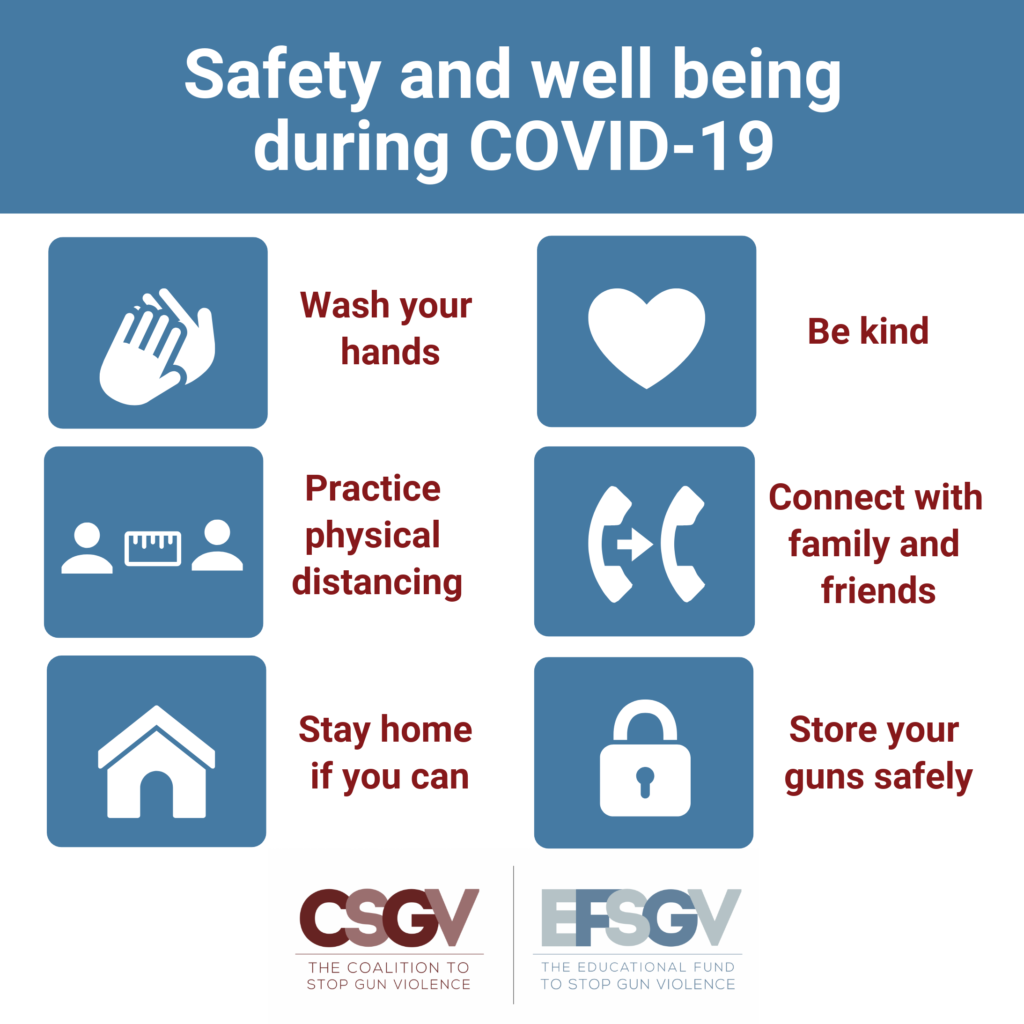

While it is imperative to practice physical distancing in order to flatten the curve and stop the spread of the virus, we do not need to practice social distancing. For our own benefit and theirs, we should make time every day to connect with family and friends online or on the phone. We should all check in on our loved ones and our community members, especially our elders, to ask how they are doing and provide support and companionship in a safe and responsible manner. The Coalition to End Social Isolation and Loneliness has compiled resources on the effects of physical distancing and how to stay connected to others during isolation.

Americans Under Stay At Home Orders

Economic Uncertainty

The COVID-19 pandemic has sparked economic uncertainty. Half of all Americans report being worried they will be laid off or lose their job and 39% of adults say they have already lost their job, lost income, or had their hours reduced without pay due to the pandemic. Indeed, in just the last three weeks (from March 15 to April 4), nearly 17 million Americans filed for unemployment benefits and a recent analysis by economists at the Federal Reserve’s St. Louis district projects a total employment reduction of 47 million, translating to a 32.1% unemployment rate. While we don’t know how long the pandemic will last nor the long-term economic impacts, we do know that the stock market is suffering, unemployment has reached a record high, and many Americans lack the financial resources to pay upcoming bills.

Research has found that suicide rates increase during economic recessions and periods of high unemployment rates, job losses, and economic instability. Economic and financial stress and uncertainty, marked by job loss, long periods of unemployment, less income, difficulty paying for medical, food, housing expenses, as well as the fear or expectation of financial stress, may increase the risk the suicide. Additionally, a recent study using the Consumer Sentiment Index, which measures people’s perceptions of their financial situation and the general economy, found a correlation between the way people view their own economic situation and the suicide rate: the more negatively people view their economic situation, the higher the suicide risk. As COVID-19 altered daily life in the United States, the Consumer Sentiment Index dropped 11.9 Index-points in March 2020, the fourth largest one-month decline in nearly a half century.

In following with the research, strengthening household financial security, such as unemployment benefits, livable wages, medical benefits, and disability insurance, is considered an important suicide prevention opportunity and is supported by the CDC. As a way to counteract economic uncertainty, Congress passed the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act which includes a stimulus payment of $1,200 to most Americans, temporarily expands unemployment benefits, and suspends payments and interest on federal student loans, among other provisions. Swift action to distribute these payments and continued legislation to expand the financial safety net will help to further reduce suicides.

Escalating Stress

Isolation and loneliness, especially when coupled with uncertainty about the future and the economy, can lead to increased anxiety and stress. The majority of Americans are reporting personal stress as a result of the pandemic. According to an ABC News/Washington Post poll, more than one in three Americans are calling it “serious stress.” The connection between stressful life events and suicide is well-established. When stressors escalate, compounded with one another, or have a negative impact for a prolonged period of time, the distress they cause can increase a person’s risk for suicide.

Stress during this pandemic may worsen due to fear and worry about your own health and the health of your loved ones, personal finances and the economy, barriers to primary care, and new or strained family dynamics. This may lead to changes in eating patterns, difficulty sleeping or concentrating, worsening of chronic physical or mental health problems, and increased use of alcohol, tobacco, or other drugs.

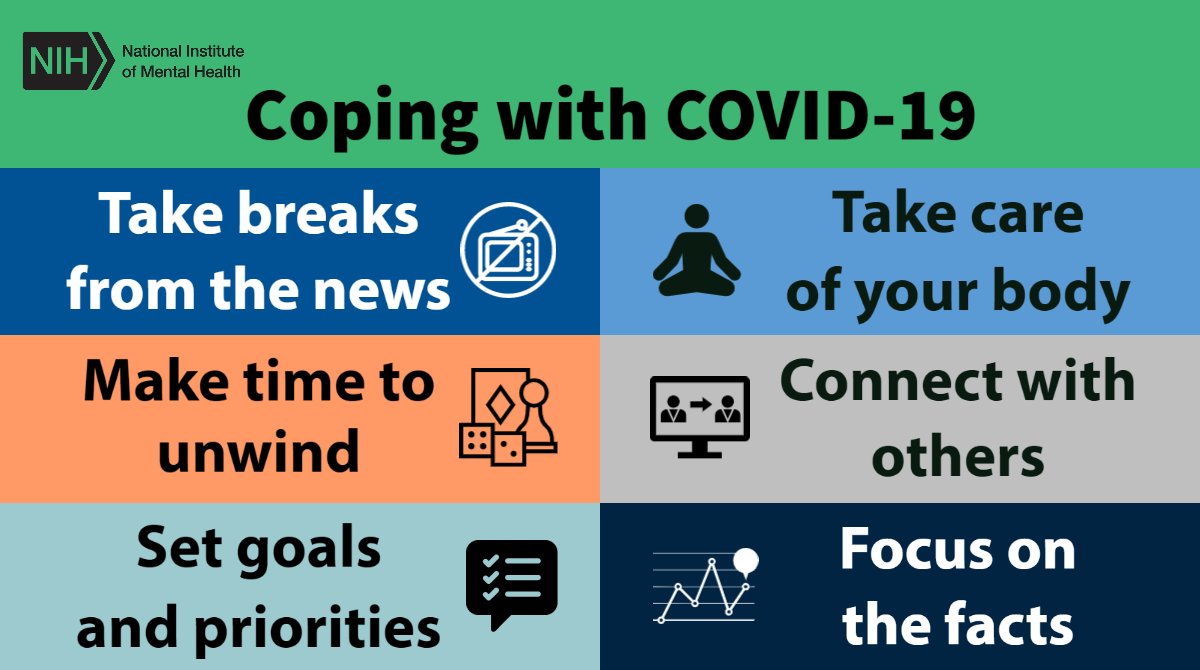

It is important to recognize the risks and role of stress in suicide. The CDC has developed a resource page for stress and coping with COVID-19. The CDC recommends coping with stress in a healthy manner by taking breaks from the news, exercising, eating healthy foods, doing activities you enjoy, and connecting with loved ones. The National Institute of Mental Health published a similar guide, which adds to the CDC’s recommended approaches to coping with COVID-19 related stress, and includes making time to unwind, setting goals and priorities, taking care of your body, and focusing on the facts.

Alcohol Consumption

Alcohol consumption has long been used as a coping mechanism and in dealing with stressful life events. Numerous studies have found increased alcohol consumption in response to exposure to catastrophic events or other disasters, including during the aftermath of 9/11 and Hurricane Katrina, among others. While drinking in moderation may not necessarily raise concerns, it is important to recognize the interplay of alcohol and suicide.

Both acute alcohol intoxication and chronic risky alcohol use have well-established associations with suicide. Risky alcohol use increases the risk of suicide and suicides are more likely to involve firearms when alcohol is involved. Alcohol intoxication can decrease inhibitions, impair judgement, and lead to impulsive or violent behavior. Further, alcohol use may intensify suicidal ideation by worsening mental health problems and interpersonal conflicts.

During the coronavirus pandemic, people may turn to alcohol as a way to cope with physical distancing, periods of loneliness, and existential stress. While we are still in the early days of physical distancing, there is already some evidence around the increase of alcohol sales, which could be a proxy for increased alcohol consumption. According to Nielsen data, alcoholic beverage sales increased 55% nationwide during the third week of March as compared to last year. Online alcohol sales are especially surging. During the week of April 6, Drizly, an ecommerce alcohol marketplace, saw a 476% increase in sales compared to the eight week prior.

Again, while moderate alcohol consumption may not necessarily raise concerns, monitoring consumption and engaging in coping mechanisms aside from drinking alcohol are proactive, healthy steps for us and those around us. If concerns about alcohol use arise, there are resources available. For example, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism created an “alcohol treatment and social distancing” resource page to share professionally-led treatment and mutual-support group options during physical distancing. For people in recovery from alcohol misuse, physical distancing may make it difficult to attend or access their usual support groups, such as Alcoholics Anonymous. In order to make support accessible during physical distancing, Alcoholics Anonymous has begun hosting live video meetings.

Firearm Access

In combination with increased isolation, economic uncertainty, escalating stress, and increased alcohol use, firearms access can increase suicide risk. Research consistently shows that access to firearms increases the risk of suicide – especially when a firearm is stored loaded and unlocked. Access to firearms in the home increase odds of suicide more than three-fold.

While firearm ownership does not make a person more suicidal, firearm access increases the risk that an individual will die by suicide if they attempt. Firearms are so dangerous when someone is at risk for suicide because they are the most lethal suicide attempt method. Suicide attempts with firearms are nearly always lethal, whereas attempts with the other most commonly used methods are lethal less than 2% of the time.

Additionally, the more time it takes someone to attempt suicide, the more time there is for someone to change their mind about attempting. Though research shows that few individuals substitute means for suicide if their preferred method is not available, if firearms are not available, the person at risk for suicide is much more likely to survive even if they attempt using another method. Delaying a suicide attempt can also allow suicidal crises to pass and lead to fewer suicides. Ninety percent of individuals who attempt suicide do not eventually go on to die by suicide.

It is reported that gun sales are currently surging due to the coronavirus pandemic. On March 28, the Department of Homeland Security classified “workers supporting the operation of firearm or ammunition product manufacturers, retailers, importers, distributors, and shooting ranges” as “essential critical infrastructure workforce.” Despite the majority of businesses being forced to close across the country, at least 38 states have deemed gun stores “essential” and they remain open. Moreover, it is estimated that gun dealers sold about 2.6 million firearms in March alone.

Comprehensive Suicide Prevention

Reducing Access to Firearms

We are living in unprecedented times. As risk factors for suicidality are on the rise, it is more important than ever to take a comprehensive approach to suicide prevention. Strengthening economic supports by giving Americans stimulus checks, robust unemployment, and other financial safety net benefits; taking time to connect with loved ones by phone or online; picking up groceries for our immune compromised neighbors; calling a support line when needed; moderating or avoiding alcohol consumption; and reducing access to lethal means, including firearms, are all important suicide prevention strategies.

In particular, reducing access to lethal means is a lifesaving suicide prevention tool. Reducing access to lethal means is the act of putting time and space between someone who may attempt suicide and lethal methods, such as firearms. Research from across the world has found that reducing access to lethal means is an effective suicide prevention strategy and an international panel of experts concluded that limiting access to lethal means was one of just two interventions with strong evidence of reducing suicide rates.

A multilevel approach for suicide prevention that addresses access to firearms can save lives. Safer storage of firearms, lethal means safety counseling, gun shop projects, and extreme risk laws are all effective interventions that should be considered during this pandemic. Taken together with upstream interventions such as those highlighted above, a multilevel approach for suicide prevention that addresses access to firearms can save lives.

Prevention Interventions

Safer Storage

Now more than ever, it is important to practice safer firearm storage. If a person chooses to store their firearm in the home, it is widely recommended to store firearms locked and unloaded, store and lock ammunition separately from firearms, and ensure the key or lock combination is inaccessible to the person at risk of suicide.

Storing firearms outside of the home is the safest option when a person is at increased risk of suicide. People can voluntarily give their firearms to friends or family members (depending on state law), a federally licensed firearms dealer, or a local police department. In some states, universal background check laws may limit the persons to whom a firearm can be legally transferred for temporary safer storage, so it is important to check state and local law to ensure the temporary transfer is permissible. If seeking storage options with a local police department, always call ahead to verify their preferred procedures.

For more information, Lock to Live provides resources about the options for safer firearm storage and helps you navigate those choices to determine the best options to keep you and your loved ones safe.

Store firearms unloaded and locked

Store and lock ammunition separately from firearms

Ensure the key and/or combination is inaccessible to the person at risk of suicide

Temporarily remove firearms from your home

Lethal Means Safety Counseling

Health care providers have an important opportunity to engage in firearm suicide prevention by providing lethal means safety counseling to patients or parents of pediatric patients who may be at risk of suicide. Lethal means safety counseling is a process that healthcare providers undertake to help patients and their families or friends find ways to reduce access to lethal means of suicide attempt, at least temporarily, during times of elevated risk of suicide. They first work to determine if a person at risk of suicide has access to lethal means, like firearms. The provider then works with the person and their family or friends to reduce access until the risk of suicide decreases.

As many people turn to telehealth during COVID-19 for non-emergency procedures and appointments, it is important for healthcare professionals to ask about firearms access and engage in lethal means safety counseling for patients at an elevated risk of suicide, such as someone who is experiencing depression or engaging in risky alcohol use, and especially if they have disclosed suicidal ideation or attempt. Behavioral health crisis services in particular should be engaging in lethal means safety counseling. The Suicide Prevention Resource Center has developed resources for telehealth professionals during this time, which includes guidance on safety planning and reducing access to lethal means: Treating Suicidal Patients During COVID-19: Best Practices and Telehealth and 3 Tips for Using Telehealth for Suicide Care. Zero Suicide has also developed a resource for telehealth professionals: Telehealth Tips: Managing Suicidal Clients During the COVID-19 Pandemic.

For more information on lethal means safety counseling, UC Davis Health’s What You Can Do initiative provides resources to help health care providers get comfortable identifying risk for firearm injury and death and talking about firearms with patients when clinically relevant.

Locked: “Is it locked?”

Loaded: “Is it loaded?”

Little children: “Are there

little children present?”

feeling Low: “Is the

operator feeling low?”

Learned owner: “Is the operator

learned about firearm safety?”

Gun Shop Projects

As many gun stores remain open, it is imperative that they have firearm suicide prevention educational materials prominently displayed and available for their customers. Gun shop projects provide local retailers, instructors, and customers of all experience levels with firearm suicide prevention educational materials. These materials include education on the elevated risk of suicide to the gun-owning community and strategies for prevention that allow gun owners to take an active role in suicide prevention among their peers.

For more information, the Means Matter program at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health’s website has a section dedicated to firearms instructors. In addition, the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention and National Shooting Sports Foundation have partnered to develop educational materials for gun owners; see their brochure on firearms and suicide prevention.

Extreme Risk Laws

Extreme risk laws are an evidence-based, bipartisan-supported state policy that establishes a new kind of protection order that temporarily prohibits the purchase and possession of a firearm and/or requires the removal of firearms from persons demonstrating behavioral risk factors for harming themselves or others. Law enforcement and, in some states, family or household members, among others, may request that a court issue an order. Nineteen states and the District of Columbia have extreme risk laws, and all but two (New Mexico and Virginia) are currently in effect.

Many states have provided explicit guidance on how to obtain an extreme risk protection order during the COVID-19 pandemic. Check in with local law enforcement and courts for further direction.

For more information, the Bloomberg American Health Initiative Implement ERPO (Extreme Risk Protection Order) site has resources for law enforcement seeking to implement extreme risk laws in their state.

Bottom Line

While COVID-19 is the most prominent public health emergency of the current day, there is another ongoing public health crisis in the United States: firearm suicide. Though these two crises may initially seem unrelated, the two share several common threads — and the same framework for a solution. As we continue to face this unprecedented and uncertain time, it is important to prioritize firearm suicide prevention. Reducing suicide risk factors such as loneliness, economic uncertainty, escalating stress and distress, and risky alcohol use while also limiting access to lethal means, such as firearms, is key to ensuring that COVID-19 does not further exacerbate firearm suicide in the United States. We at the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence and Educational Fund to Stop Gun Violence are committed to making gun violence rare and abnormal, and our work does not stop with the COVID-19 pandemic; instead, it has become even more essential.

Resources

Crisis Lines

Disaster Distress Helpline: 1-800-985-5990

Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 1-800-273-8255

Suicide Prevention Lifeline (Spanish): 1-888-628-9454

Suicide Prevention Lifeline (Deaf, Hard of Hearing, Hearing Loss): 1- 800-799-4889

Suicide Prevention Lifeline Chat

Crisis Text Line: Text 741741

NAMI HelpLine: 800-950-NAMI (6264)

Trans Lifeline: 877-565-8860

Trevor Lifeline (for LGBTQ youth): 1-866-488-7386

Trevor Text: Text “Trevor” to 1-202-304-1200

Veterans and Service Members Crisis Line: 1-800-273-8255, Press 1

Veterans and Service Members Text Line: Text to 838255

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)’s National Helpline: 1-800-662-HELP (4357)

Mental Health

Behavioral Healthcare Resources – COVID-19

AARP: How to Fight the Social Isolation of Coronavirus

CDC: Stress and Coping During COVID-19

Child Mind Institute: Talking to Kids About the Coronavirus

NAMI: COVID-19 Resource and Information Guide

Pandemic Crisis Services Coalition: Resources related to mental health, suicide prevention, crisis intervention, and COVID-19

Psych Hub: COVID-19 Mental Health Resource Hub

SAMHSA: Coronavirus (COVID-19) guidance and resources

Suicide Prevention Resource Center: Resources to Support Mental Health and Coping with the Coronavirus (COVID-19)

Youth Suicide Research: Parenting Resources for Suicide Prevention in Teens during Covid-19

Other Resources

Firearm Safety Among Children and Teens (FACTS): Family Guide to Home Firearm Safety During COVID-19

This page was last updated April 2020.